NYC pension gimmick alert

Governor Hochul has slipped some dubious New York City pension "amortization" language into her FY2026 state budget amendments.

On the day she announced a half-baked plan to sort-of, kind-of undermine and stigmatize Mayor Eric Adams rather than either (a) remove him from office, or (b) leave him alone, Governor Kathy Hochul quietly did the mayor a big fiscal favor (at least in the short term, maybe). Then again, maybe the mayor isn’t the only beneficiary she has in mind.

Late Thursday, Hochul’s 30-day state budget bill amendments included a technically complicated piece of legislation designed to reduce city pension costs by $1.3 billion this fiscal year and next, and by another $9.6 billion over the following six years. The change would affect the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS), which has $90 billion in assets and covers 350,000 active and retired employees; the New York City Teachers’ Retirement System (NYCTRS), which has $285 billion in assets covering 200,000 active and retired employees; and the much smaller Board of Education Retirement System (BERS), which has 58,000 active and retired members and $6.3 billion in assets.1

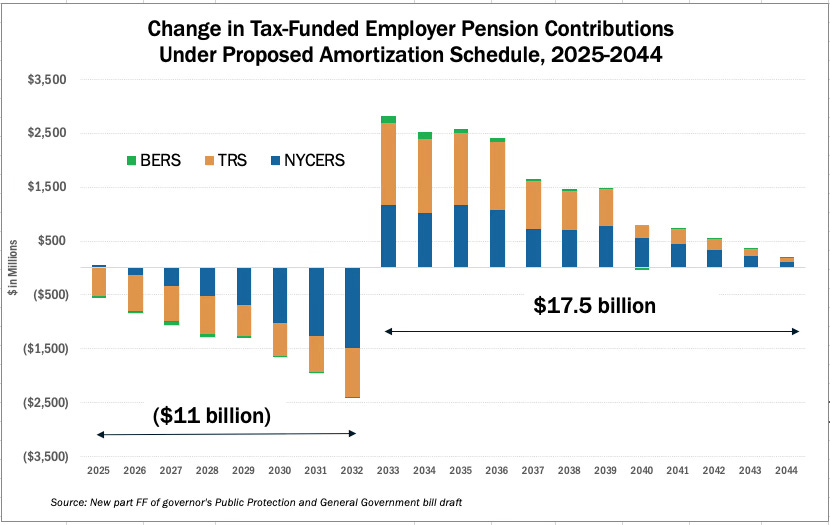

As depicted below, total savings under this proposal are projected at $11 billion through fiscal 2032. But after that, it will be time for payback—a big payback. From fiscal 2033 through 2044, pension costs will rise nearly $18 billion higher than the levels that would be projected under current standards.2 In other words, this is a classic save-now, pay-later scheme.

(Note: As I dug more deeply into city pension fund actuarial reports following this post, I realized that the chart above—while numerically accurate in every respect, as derived from the fiscal note in the governor’s bill language—presented only a partial picture of how the change would affect projected contributions. For a clearer perspective, see this chart and this chart from my March 17 follow-up post.)

In the past, statutory changes to city pension fund assumptions were introduced by the chairs of the relevant Assembly and Senate committees, passed with little or no debate, and were quickly signed into law. This kind of thing has never previously been embedded among a governor’s Article 7 budget bills, where it doesn’t belong.

Borrow now, pay later

The last time New York officials monkeyed with pension amortization to reduce short-term employer contributions was in 2010 via the Contribution Stabilization Program, which gave the state government and local municipalities the option of paying only a portion of their annual pension contributions to the Fund when due, spreading the rest over time with interest. Danny Hakim of The New York Times described it as “classic budgetary sleight-of-hand”—since employers would in effect be borrowing from the pension fund itself with a promise to repay the loan later. “Call it what you will,” said then-Lt. Gov. Richard Ravitch, “it’s taking money from future budgets to help solve this year’s budget.” As it happened, the state lucked out: the risky “stabilization” program didn’t leave fiscal scars because the stock market strongly recovered in the years that followed.

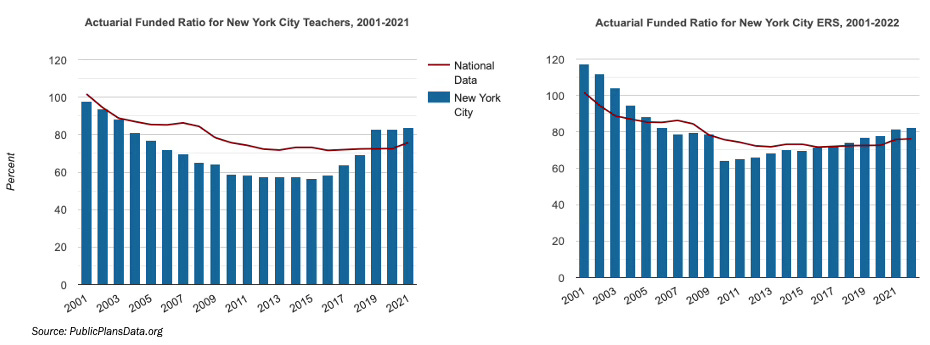

The circumstances now are much different. Adams’ FY 2026 financial plan projects modest growth in pension costs, from $10 billion this year to $11.8 billion in fiscal 2028, thereafter dropping to $11.3 billion in fiscal 2029. All of this assumes, of course, that the fund hits its targeted 7 percent rate of return on investments. Meanwhile, as shown below, since the end of the Great Recession both NYCERS and NYCTRS have made progress toward fully funded status. Assuming the financial markets and economy don’t go into a prolonged slump, these pension funds are still several years away from getting back to 100 percent.

This gets back to the question of why. With key metrics headed (if slowly) in the right direction, why mess with pension financing now?

Look for the union label

Hochul’s amortization proposal is of strong interest to the two largest unions whose members belong to the pension funds in question—District Council 37 of AFSCME and the United Federation of Teachers (UFT). Indeed, it’s safe to assume nothing like this would see the light of day if Henry Garrido and Michael Mulgrew weren’t supporting it—assuming they aren’t, in fact, actively lobbying for it.

A few more pension basics: for purposes of calculating the annual contribution due from employers (i.e., taxpayers), pension liabilities (the total retirement payments promised to all employees vested in the system) are discounted at a rate matching the system’s expected annual return on its investments. A higher assumed investment return equates to a higher discount rate—and the higher the discount rate, the less the employer needs to contribute each year to cover newly accrued benefits for current employees.

In the 1990s, the discount rates of public pension funds across the country peaked at more than 8 percent, which proved to be excessively optimistic once the tech bubble burst in 2000, followed by the 2002 stock market downturn, and finally the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2007-09. (Private pension plans also invest in the volatile equities market, as well as other assets, but are required by federal law to calculate employer contributions based on lower (and hence more prudent) discount rates, benchmarked to Treasury bills and highly rated corporate bonds.)

In early 2013, the Legislature passed and then-Governor Cuomo signed a bill reducing the city pension funds’ assumed rate of return at 7 percent. With no further change to pension actuarial assumptions, this would have created a larger unfunded accrued liability, or UAL, which in turn would have required an immediate and sizable increase in taxpayer-funded employer pension contributions. To cushion the blow, the law (Ch. 3 of 2013) provided that the additional cost of the lower discount rate would be “amortized” over 22 fiscal years, based on the UAL as calculated in 2010. In each of those 22 years, employer contributions would include an extra amount representing 3 percent of the UAL. The amortization period is due to end in 2032.

The bill Hochul backs would extend this existing amortization period out to 2044 for the NYCERS, NYCTRS, and BERS. But why bother? What’s the pressing need here?

As noted above, in contrast to fiscal and economic conditions prevailing in the wake of the Great Recession, pension costs aren’t skyrocketing. Both NYCERS and TRS have come close to hitting their 7 percent targets over the last 10 years, most recently earning a 10 percent return in fiscal 2024. If the stock market continues to perform well, pension costs will continue to decline. Of course, there’s always a very real risk that the markets will tank, in which case costs will rise again. But even under that scenario, the scheduled end of the current UAL amortization period will provide some added relief in seven years. The proposed amortization extension would wipe that out.

If the Legislature approves Hochul’s proposal, the money saved by the city is most likely to be spent on salary increases. The DC 37 contract expires in November 2026, and the UFT contract a year after that; in the meantime, despite falling public school enrollment, the city must hire and pay thousands of additional teachers to comply with a class-size reduction mandate signed into law by Hochul in 2022.

So far, neither Hochul nor Adams has publicly explained or offered any justification for this maneuver. In the meantime, the late Dick Ravitch’s words bear repeating: “Call it what you will, it’s taking money from future budgets to help solve this year’s budget.” *

*After this was initially posted, Governor Hochul’s office released this concerning the pension proposal:

“At the request of New York City, this proposal is an extension of the timeframe to fully account for unfunded obligations within the New York City pension system which were first recognized in 2010. This proposal will have no impact on the State financial plan, fully supports the NYC pension system, and will mitigate volatility by extending the period of recognizing these costs.”

Pointedly excluded are the city’s separate Police Pension Fund and Fire Pension Fund.

These, it should be noted, are nominal values. On a net present value basis, assuming the pension funds achieve their 7 percent annual return target, the changes even out at $8.226 billion in savings in the first eight years, and $8.226 billion in costs over the last 12. That’s how the thing is justified in the actuarial universe. (Thanks to Mary Pat Campbell for the NPV calculation.)

Mulgrew’s fingerprints are all over this spend now pay later scheme particulariy since no one has any idea of what the money will be used to pay for. And Mulgrew is up for re-election and having lost the Retired Teacher Chapter election to the opposition, he surely wants to come up with something big to look like a hero. The same hero who raided the Stabilization Fund of a billion dollars to pay for raises in 2014. The same dirt bag who has fought and lied for just about 4 years to take away 250,000 NYC public service retirees healthcare promised over the decades that they worked for NYC.

From yesterday’s UFT executive board meeting.

Tom Brown responded, somewhat hostilely, suggesting that bad information was out there. He said that no one was borrowing money from the pension system and that the piece of legislation was merely a correction or ‘smoothing out’ of previous actuarial estimates. He suggested that during a period of time, contributions were overstated, and that this move was about recuing volatility. It has no baring on pensions of current retirees or future retirees and has no bearing in calculations. He went on to discuss how the TRS had been around since 1917 and had never missed a payment, again, going on a bit of a sarcastic diatribe over bad information out there.